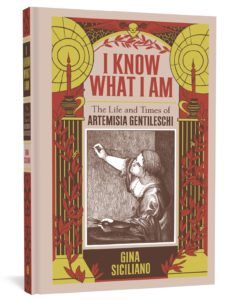

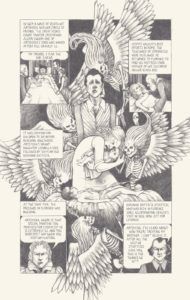

Artemisia’s art is startlingly different from that of her male contemporaries. She tended to feature images that today read as inarguably feminist: forgotten heroines of the Bible and mythology brutally attacking men, carrying their severed heads, or cringing at their inappropriate advances. Best known of her work is her brutal, blood-spattered Judith and Holofernes. This image of a woman intent on brutally murdering a seemingly helpless man, as her female servant stands nearby to assist, can be found today printed on leggings, crop tops, and other novelty items. Unlike the comparatively staid versions of these same characters as painted by male painters, Artemisia’s version of the scene is visceral and somehow modern. Learning about her experiences as a talented woman braving a male-dominated field in a patriarchal culture brings her work into a new context. As a teenager, Artemisia was raped and brought charges up against her attacker. The ensuing trial found her subjected to a brutal cross-examination that questioned her role in her own attack. Artemisia continued working, painting for wealthy patrons, for decades afterward, crafting a substantial body of work. Her attacker, also a painter, also continued to work, but his name and works are now mostly obscure. I Know What I Am provides a complex, feminist portrait of Artemisia as a single mother, a sexual assault survivor, and a pioneering practitioner of her craft. More than a biography, this work is a resource for readers to immerse ourselves in the unforgettable story of Artemisia Gentileschi. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Ann Foster: Why do you think Artemisia Gentileschi’s story has become so much more talked about lately than it has been in the past? Gina Siciliano: In Jesse Locker’s wonderful book Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting, he refutes the idea that Artemisia was unknown and forgotten by examining a number of 18th century written references to her. He shows that she actually did receive a brief wave of mid–18th century recognition. Then again her name came up among Caravaggio scholars during the first half of the 20th century, and even some acknowledgment of her struggles as a woman with Anna Banti’s 1953 novel about her. The feminist wave of the ’70s and ’80s really kicked off Artemisia’s fame as a pioneering female artist and sexual assault survivor. Mary Garrard deserves a lot of credit for this, as she wrote the first monograph on Artemisia in the early ’80s, with an English translation of the rape trial [ed. note: this book is Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art]. On top of all this, the new 2019 surge of interest in Artemisia has to do with the #metoo movement of course, and the lightning speed with which information and ideas spread through the internet. Also, us feminists have been working for years to change the dialogue about sexual assault and women’s art history, and it seems like a lot of our claims are finally trickling into the mainstream now. AF: What is your relationship to Artemisia Gentileschi’s life and work? Were you familiar with her story and her work before you began working on this book? GS: I discovered Artemisia in a general Western art history class at Pacific Northwest College of Art. I was immediately drawn to her, her story is just so naturally compelling and inspiring, and of course I could relate to it. I saw that her work was like nothing else, it has always stood out immensely. Then, after I graduated in 2007 I saw the [Judith and Holofernes] painting at the Ufizzi, and I knew I wanted to make a graphic novel about her life and work. However, it took a while longer for me to be ready to tackle the project, so I didn’t seriously begin until around 2011, 2012. AF: In your book, you present your versions of many of Artemisia’s famous paintings. Did you discover anything in recreating these famous images, either about her style or the work itself? GS: I learned a lot by copying the paintings into the book. It required deep, intense hours of concentrating on looking and studying the images, so of course things I didn’t notice before came up in all kinds of ways. And not just in Artemisia’s paintings, but many others as well. There’s a big difference between looking at a painting for five minutes and looking at a painting for five hours! I started seeing different objects and figures emerging from the dark areas. I learned a lot about how these artists handled clothing and drapery. And I was also confronted with the great mysteries of this art—the areas of the paintings that haven’t survived as well through all these years. Also, the expressions of the figures in the paintings took on new life—at times I felt as if I was seeing the models trying to hold the poses for the artists, like glimmers of their expressions. A lot of this made me want to see more of the paintings in person so badly. AF: Artemisia’s early life is entirely derailed by her experience of sexual assault, which you present viscerally yet tastefully in this book. What were your considerations for creating the images to present the horror of this experience? GS: Handling the sexual assault in the book was a totally natural, intuitive process for me. Artemisia described her experience in detail during the trial, so my biggest goal was just to stay as true to her words as possible. I could visualize the whole thing easily, as with most of the material in the book. It was one more story that played out in my mind as I did the research. I also set out to put her experience within the context of her time and place, while simultaneously addressing common misconceptions about sexual abuse. Plus, some scholars have written about how the impact of the abuse would have been different for a woman in 1612 than for us in the 21st century, which is certainly true. Yet, I think she still suffered and she’s still an important heroine. So the question that comes up a lot is what feelings do we have that are intrinsic to being human across the ages, and which feelings are solely the product of their time and place? AF: Your book includes not just the gorgeous graphic novel, but also lengthy endnotes and a full bibliography. Did you know going in that it would include this much non-comics material? And if not, at what point did you realize the benefit of including these resources along with the comic? GS: The addition of the notes section was another aspect of the project that came about naturally and intuitively. As I touch on in the Preface, I didn’t want to create another sensational story based on Artemisia or use her as a jumping-off point for my own agenda. I wanted to give readers more concrete history. I wanted to piece together what Artemisia was like, and to do that I felt that I would have to delineate for readers what is me and my interpretation, what is Artemisia’s actual voice, and what is other peoples’ interpretations. When I started writing and thumbnailing and working with an editor I realized pretty quickly that all of that is just too dense for a graphic novel of this length. But the only way I could get comfortable cutting out large swaths of material was by knowing that it would still be there in the notes section. So the more I learned, the larger the notes section got, especially since I continued reading and doing research throughout the whole process. Also, on a more practical level, I’ve never had the money or resources to dig through far-away archives, so all my sources are secondary. That means that I used a lot of other people’s research, so I really need to give credit where credit is due, and the notes section/bibliography is a great spot for that. In addition, the notes are an extension of my feeling that people need to reconnect with history, and history is always biased depending on who is telling it. So we need to constantly analyze where our history comes from and how it’s told. To me, that’s a big component of feminism, and our efforts to rethink race, class, and gender. Another way to think about it, especially regarding the retelling of the sexual abuse, is that we can piece together Artemisia’s story through research, but a lot of times we piece together Artemisia’s history through gut feelings and emotional responses to her life and work. I wanted to do something based on research, but without completely disregarding the gut feelings and emotional responses. In my opinion, we need to utilize both of these—If we are only driven by emotional responses and gut instincts, then we’re missing the big picture and we aren’t doing justice to Artemisa and her legacy. On the other hand, if we totally disregard the gut instincts and emotional responses, then it’s harder to feel deeply connected to and inspired by Artemisia and her legacy. I really hope this makes sense. AF: If Artemisia Gentileschi were to come of age today, what do you think she would be like? What sort of artistic expression do you think a 21st-century Artemisia might be drawn to? GS: I rarely ever think along these lines because I’ve worked so hard to situate Artemisia within her own time and place. At this point, I can’t separate her from her world at all, which is why the subtitle is “The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi.” It’s impossible to know who Artemisia would be outside of her place in history, and to me what’s most interesting is what she accomplished despite of and because of the Italian Renaissance/Baroque era. AF: Thank you for answering our questions today, Gina! Looking for more Artemisia Gentileschi? Try our post 10 Quotes From Blood Water Paint That Feel Like A Gut Punch.