A Brief Bio of the Bard

Church records for the town of Stratford-upon-Avon confirm that a baby named William, son of John and Mary Shakespeare, was born in April 1564 and died in April 1616. In between 1564 and 1616, William pops up a few times in legal cases and other historical records. We know he married and had three children, he acted and lived in London for a time, and his name was attached to a bunch of plays and sonnets. We know that rival playwright Robert Greene once wrote that he was an “upstart crow.” And…that’s about it. We know almost nothing else about the man William Shakespeare. We don’t know when he started writing or how he died. We don’t know how he spelled his name — signatures exist showing several different spellings — or even what he looked like. Both portraits that historians think depict Shakespeare were completed after he died. Added to all that, in 16th century London, when Shakespeare was around, copyright was not as firm a concept as it is now. Many plays were never published in written form, and playwrights borrowed from one another’s work constantly. In fact, many Shakespeare plays, such as The Taming of the Shrew, feature entire plots lifted from earlier works by other authors. Original hand-written manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays did not survive. The plays were only collected and published after his death, by actors John Heminges and Henry Condell, who published them in 1623 as a book known as the First Folio. Given that Shakespeare’s plays are wildly popular and influential, and he is widely acknowledged to have been a genius, yet we don’t know anything about him or have his original manuscripts…you can see why people might start to wonder if this mysterious figure actually wrote the plays.

The Case for Someone Else as Shakespeare

What can we learn about Shakespeare from his plays? Many are set in Italy and ancient Greece and Rome. They’re full of dazzling wordplay, phrases that had never appeared in print before, memorable characters, and allusions to the Bible and other works of literature. All this suggests that their author may have been well-educated and well-traveled, possibly even someone who could read Latin and speak French and Italian. Here’s where the trouble begins. William Shakespeare was born to a pretty ordinary family. His father, John, was a glover (glove maker) who later entered local politics; his mother, Mary, was from an established local family. Little Will would have received a standard education at the nearest grammar school, learning the basics of Latin and classical literature. He doesn’t show up as a student in university records; we know that other prominent playwrights of the time, such as Christopher Marlowe, did attend university. It’s likely that Shakespeare didn’t even travel beyond his hometown until he turned up in London in 1592, where records show he was working as an actor. Some historians have argued that this basic education and lack of travel show that Shakespeare simply was not capable of writing the plays. Aside from being snobby and elitist, this argument seems to overlook human nature. Genius does find a way, education or not. You only have to look at other authors, like Jane Austen, to know that it’s possible for someone to write literary works of lasting popularity without attending university or traveling far. Nevertheless, this is a cornerstone of the “Shakespeare didn’t write these plays” argument. So…who did?

Secret Shakespeares

Here are three of the leading contenders for the role of “true author of Shakespeare’s plays.”

Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593)

Marlowe, born in 1564 in Canterbury, was one of the most famous playwrights of the Elizabethan era. He and Shakespeare likely knew each other. Marlowe was the author of such contemporary hits as Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine, but unfortunately he was also caught up in spying and the troubled politics and religious disputes of the time (unlike Shakespeare). These entanglements may have led to Marlowe’s death at the age of just 29. Though he “officially” died in a tavern brawl (an Elizabethan bar fight), there are many theories that his death was orchestrated as a cover-up or to protect members of Queen Elizabeth’s inner circle. A theory first put forth in the early 19th century argues that Marlowe faked his own death and continued to write plays under a name borrowed from a certain London actor he knew. And Marlowe died just before Shakespeare’s name was first associated with a published piece of writing (the narrative poem Venus and Adonis). “Shakespeare,” or Marlowe in disguise, then went on to become a popular playwright. Problems with this theory? No one at the time doubted that Marlowe was truly dead. And more tellingly, Marlowe and Shakespeare had clearly different writing styles. In vocabulary, themes, use of some poetic techniques, and even subject matter, the two differ. There’s no doubt Shakespeare’s writing was influenced by Marlowe, who was the most important playwright of the time. But it’s hard to believe that a famous writer faked his own death to become another famous writer, and no one in their small literary and dramatic circle found out about it.

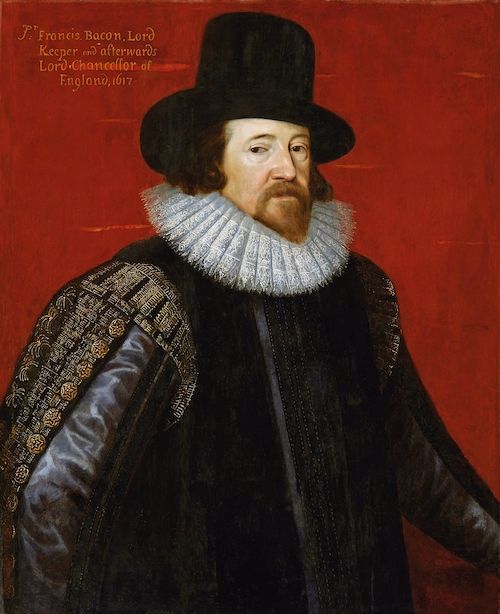

Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

Sir Francis Bacon was a well-educated member of the aristocracy who dabbled in natural philosophy, science, politics, and poetry. He held a number of positions in Queen Elizabeth’s court and had a good deal of power and a lasting influence on English philosophy and science. Was he also the author of the world’s most famous plays? There’s no evidence to suggest he isn’t, but equally there’s no evidence to suggest he is. The theory seems to have started with an American woman named Delia Bacon (no relation) in the early 19th century. Her argument is that a man who held various important positions in the Elizabethan government couldn’t have been associated with something as vulgar as the theatre, so he had to hide his true love of writing raunchy comedies and bloody tragedies. But Bacon was already a writer under his own name, and scholars argue that his less-than-thrilling surviving attempts at poetry and dramatic work show he was probably not the real Shakespeare. In fact, he once wrote an essay calling the theatre frivolous. (Plus, Bacon was already a very busy man and didn’t have time for an entire secret career on top of the four he already had.)

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604)

Perhaps the most popular candidate for “the real Shakespeare,” de Vere was a nobleman, patron of the arts, a writer (though none of his plays survive), and a competitive jouster. Like Bacon, he was a busy man and it’s hard to imagine he had the time for a secret identity. But let’s look at the evidence. Proponents of this theory, who call themselves Oxfordians, argue that some of the events in Shakespeare’s plays match events from de Vere’s life. De Vere had lived in and traveled throughout Italy. He even had a personal Bible that was heavily marked up with marginalia — supposed “evidence” that he wrote the plays, as they are full of allusions to the Bible. Verdict: unconvincing. Any member of the Elizabethan aristocracy who had been to Italy and owned a Bible is an equally likely candidate. And De Vere died in 1604, but new plays by Shakespeare continued to appear for several years after that.

Books About Shakespeare’s Identity and Tudor England

If you’re keen to read more about all the candidates and evidence yourself, there are plenty of books. Bill Bryson’s short, lively biography Shakespeare: The World as Stage provides an entertaining overview of what little we know about his life as well as the strange conspiracy theories people have invented about him. Contested Will by Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro is a deep dive into all the theories. And This Is Shakespeare by Emma Smith takes a new look at Shakespeare, examining the inconsistencies and flaws that make his writing so compelling. If you want to learn more about the times Shakespeare lived in, try Black Tudors by Miranda Kaufman, a look at the untold stories of eight Black people living in Tudor England, and England’s Other Countrymen: Blackness in Tudor Society by Onyeka Nubia, an investigation into the presence of Black people in Tudor England. How to Be a Tudor by Ruth Goodman will teach you everything you need to know about how to blend in, and Natalie Grueninger’s Discovering Tudor London will guide you through the city Shakespeare knew.

Okay, But…Who Really Was Shakespeare?

Unfortunately, we’ll never be able to definitively answer this question. I haven’t even touched on all the potential Shakespeares in this post! Our old friend Delia Bacon also proposed that a group of men including Bacon, de Vere, the explorer Sir Walter Raleigh, and others wrote the plays together. This seems supremely unlikely, but until someone discovers an old diary that says, “I wrote those plays!” signed by Billy S., anything is possible. But the evidence arguing Shakespeare was some other person isn’t very compelling; no one has satisfactorily answered the question of why someone would go to such absurd lengths to pin their life’s work, a collection of brilliant and groundbreaking plays, on some actor from Stratford. In this case, the simplest answer seems truest: the person who wrote Shakespeare’s plays was in fact the person named William Shakespeare who was alive when those plays were written. All the evidence that does exist (title pages of plays, references to Shakespeare by other playwrights of the time, theatrical records, and so on) points right back to William Shakespeare of Stratford. If you’re keen to learn more about Shakespeare, we’ve written about the beloved bard many times. We’ve argued in favor of continuing to read his plays and we’ve rounded up modern retellings based on them. We’ve even got love quotes and cross-stitch patterns for you. Don’t let the question of who Shakespeare really was stop you from enjoying his work. As Shakespeare himself might say, “The play’s the thing.”