Every autumn, John Pentecost returns to the farm where he grew up, to help gather the sheep down from the moors for the winter. Legend has it that over a hundred years ago, the Devil himself attacked John’s town, leaving thirteen dead and the survivors terrified. Each year, the townspeople redraw the boundary lines of the village, with pen and paper but also through song, dance, and rituals, which keep the sheep safe from the Devil. But as the farmers of the Endlands prepare to gather the sheep, they begin to wonder whether they’ve let the Devil in after all. The world as you know it is ending. A meteor is coming. The sun is dying. An epidemic has wiped out most of the population. Men are disappearing from the gene pool. No one can sleep any longer, and everyone is going mad. Zombies are on the march. Or you’re in the distant North, and all of the power has gone off, and you can’t communicate, so you…wait. Fearing the worst. Then knowing the worst. And still waiting. These are some of the scenarios in recent post-apocalyptic titles, from Black Moon (the insomnia story) to Ember (the sun is burning out) to Moon of the Crusted Snow (in which a northern reservation loses power, and then realizes the rest of the world has, too). They horrify us with their chaos and loneliness and with the reality of how quickly people become desperate, but they also hold us rapt, in part because something about them seems all too possible. In the aftermath of the world-ending event, the question that always rises is: what do you do if you’re one of the ones who’s left? Do you rebuild with other survivors, or escape somewhere where you’re free from the sudden violence of other, equally desperate folks? Do you become salvaging scavengers as in The Book of Etta, trading with those who are left but creating your own community separate from them that follows patriarchy-rejecting rules and revives women’s knowledge? Do you form a new family and take off in search of something better than rationed cola, as the leads in Claire Vaye Watkins’s Gold Fame Citrus do? Do VHS tapes from the world before become treasured relics, as in Woman World—even when you have no means to view them? I love post-apocalyptic novels, but would not want to survive the apocalypse. The scenarios above sound awful. I’ll take my necessary modern medicine and my functional tap and use electricity and be happy; a survivalist I am not. Still, the after scenarios appeal to me as a reader, and those that speak to me most operate from a reader’s perspective: they are the ones that find their survivors not just fighting and struggling, but also reading.

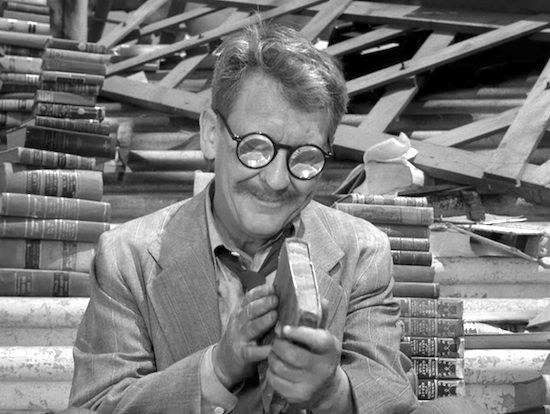

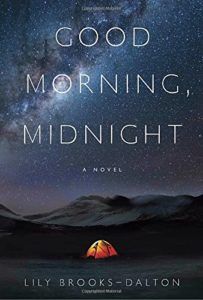

Call The Twilight Zone episode Time Enough to Last a first dose of this. Henry hates his dead end bank job, and home isn’t much better: he just wants to curl up in his chair and read, but his wife thinks that’s a waste of time, and she destroys any books that she finds. So Henry hides in the bank vault during lunch to get in a few precious pages. While he’s locked in, the world ends outside. He emerges to find everyone gone and everything destroyed…except the library. (There’s a cruel twist ending, but if you haven’t seen the episode, I don’t want to spoil it for you.) For the few precious moments in which Henry has a whole world of books at his disposal, this post-apocalyptic scenario is kind of also (morbidly) ideal. What reader hasn’t fantasized about having endless time to read, read, read? I’m always interested when the survivors of post apocalyptic novels share this same desire. We see it in Station Eleven, wherein Kirsten craves the last books she read before the plague took over. While a librarian in New Petoskey is eager to collect any book from before that comes his way, Station Eleven‘s book fare is mostly fictional itself: a pulpy Arthur Leander biography; a gorgeous and inspiring copy of the graphic novel Station Eleven, inked by Arthur’s ex. There’s also the requisite Bible, and Shakespeare plays in prominently, but the book’s most beloved titles are those that meant the most to their readers before everything went south. This thirst for the familiar also drives the readers in Good Morning, Midnight—an astronomer at a Arctic outpost and a group of returning astronauts, respectively. Arthur thinks fondly of the signed copy of Cosmos that he sent to his daughter years ago; his companion pores over left behind paperbacks in their outpost home. Aboard the shuttle, Sully’s crew can’t get enough of science fiction: The Left Hand of Darkness and Isaac Asimov both help to hold them steady as they head back to silent uncertainty on Earth. We see this in post-apocalyptic movies, too—though some, like Seeking a Friend for the End of the World, preference other media (in its case, vinyl records)—that tend to hold their paper records dear. It seems like there are two main motivations for reading post-apocalypse: the first is preservationist. You want to maintain something about a culture that is now gone. The second is nostalgic: you read something well-trod because it returns you, personally, to the time before. Even in post-apocalyptic books where reading is verboten, from The Giver to The Handmaid’s Tale, the same desire persists, whether survivors are able to address it or not. I often wonder what books I’d want most in the time after an apocalyptic event: would I choose favorites, like Leaves of Grass or The Handmaid’s Tale? Holy books, from The Tanakh to Pale Blue Dot? Something comforting from childhood, like Anne of Green Gables? Or, with the end bearing down, do you simply grab the nearest book and hope for the best? Share the books that you’ve run across within post-apocalyptic books in the comments—or say which books you’d choose for your own after library.