Libraries have been collecting fines since at least the late 1800s, originally using them to generate revenue for the library and also, in an example of strict father morality, to punish those who cannot adhere to arbitrary timelines. When researching for this article, I was surprised to learn that research on going fine-free has been published since as far back as the 1970s. Similar to other movements involved with equality and equity, it took several decades — and in this case, a global pandemic — to put the idea across the finish line.

Going back to the Before Times, despite 35 years of research, over 90% of libraries still collected fines of some sort as of 2016. In January of 2019, the American Library Association (ALA) adopted a resolution adding the following to the ALA Policy Manual:

The resolution further encouraged libraries to “scrutinize their practices of imposing fines on library patrons and actively move towards eliminating them.” The core vision of the ALA is two-fold: to advocate for the value of libraries and librarians in connecting people to recorded knowledge in all forms and for the public’s right to a free and open information society. Viewed through the lens of economic justice, it becomes easy to see how library fines would create a barrier to those who are most likely to need the library’s service: children and the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

ALA CD #38

And yet, as Sabrina Unrein states in the opening of her report, “Overdue Fines: Advantages, Disadvantages, and How Eliminating Them Can Benefit Public Libraries,” libraries have traditionally also had an aspect of public shame associated with them. After all, what happens when you speak too loudly in the library? Or when you return your books late? You may earn yourself at best a stern look from the librarian, and at worst a serious shushing or talking-to. The modern library is moving away from this model in many ways; it is becoming more of a community center, where those who want to read or study quietly can still usually find a room, and fines are well on their way to being eliminated.

In September of 2019, the San Francisco Library system announced that it is now “fabulously fine-free” to all patrons, 45 years after eliminating fines for children and teens back in 1974. The move eliminated fines from the 38% of adult patrons who owed late fines to the library and unblocked the cards of over 17,000 patrons. One San Francisco librarian at the main library branch is quoted in the report to the San Francisco Public Library Commission as saying, “I cannot emphasize strongly enough that many patrons refuse to check out books due to fears about fines. Many lower-income and poorly housed people have expressed extreme anxiety to me about the fines they have racked up.” This distress from patrons about library fines was a thread throughout all of the articles I read and librarian interviews I did for this article; if one is not experiencing economic distress, it is easy to forget how much $23 (the average fine eliminated at the SF Library) can mean to a person who is. It is the difference between eating for a day or not.

In a discussion with Michelle Jeffers of the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL), the shift to “fabulously fine-free” made the transition to closing the SF library system in March 2020 much easier than it would have. The libraries simply shut down and sent a notice to patrons telling them to keep their borrowed items until notified otherwise. As an SFPL patron myself, I borrowed a book on Indian cooking the week before everything closed down and was able to spend the first several months of lockdown discovering all the ways that chana masala makes an excellent savory breakfast food.

The SFPL reopened in mid-August 2021, and in the preceding 17 months worked with the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) to make sure every student in the city has a library card. This was, as may be imagined, a huge challenge; de-duplicating student records, updating addresses, confirming students, etc., on top of working to create library content for a population who cannot actually go to the library. The library also started using Hoopla as a digital school library, and Jeffers was pleased to note that the heat map showing Hoopla adoption was hot over the entire city. That is, students in every part of San Francisco were using Hoopla regularly.

I also spoke with Kate Sanchez of the Ocean County Library System (OCLS). She said that while OCLS had been looking seriously at going fine-free for “awhile,” they made a decision to do so in July 2020, when the system partially reopened after shutting down in March 2020. The library went officially fine-free in July 2021, and Sanchez said that the COVID-19 situation definitely pushed the OCLS to go fine-free for good. It eliminated the need to add accruing library fines to the long list of stressors library patrons were (are) experiencing. It also allowed librarians to focus on how they could continue to support their community from behind a mask and plexiglass: the OLCS YouTube page subscribership has increased by 800% in the last year and they have implemented a concierge service for recommending books, similar to Book Riot’s own Tailored Book Recommendations.

My final conversation around the connection between COVID-19 and the elimination of library fines was with Michelle Simon, Deputy Director of the Pima County Public Library (PCPL) in Tuscon, Arizona. The PCPL experience mirrored that of OCLS in many ways; they had been researching and looking at going fine-free for several years, and the onset of lockdown got the proposal across the finish line sooner than it might have done under other circumstances. PCPL went officially fine-free on July 1, 2020, eliminating fines for their adult patrons and unblocking accounts for over 50,000 library cardholders. The report cited the success stories from other libraries across the country, and pointed out that under the fine structure, and adult who had the maximum number of items checked out would accrue $12.50 per day in fines. The library’s main concern was, again, the inequity of the economic impact of fines on its patrons. Simon said, “going fine-free is about eliminating barriers to the library. The map of our patrons in socioeconomic distress was exactly the same as the map of patrons with high library fines.”

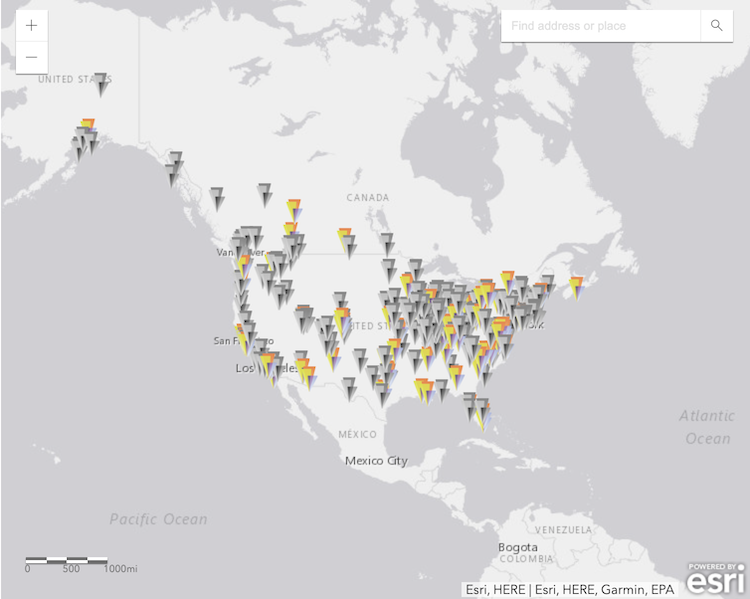

Many of the library reports I found cited the Fine Free Libraries Map, hosted and updated by the Urban Libraries Council. Here is an image from the PCPL fine-free recommendation report, showing fine-free libraries across North America in April 2020:

And here is a screenshot of the map in August 2020:

It is clear that the elimination of library fines is a growing trend, and rightfully so. When we consider that the total amount of library fines collected prior to policy changes added up to to less than one half of one percent of each library system’s budget, the way forward seems clear. Community concerns about eliminating fines were almost nil, according to the three sources I spoke with, and amounted to distress that not being fined would not help teach social responsibility.

To that, Michelle Jeffers of the SFPL responded, “The library’s job is not to teach that kind of responsibility. It’s to provide equal access to information and education.”