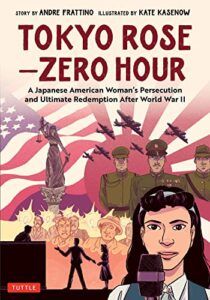

Historically, comics have done an incredibly poor job of depicting Asian characters. Thanks to a combination of wars and already existing racial bias, Asian characters in comics — including not just Japanese, but also Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese characters — have often been one-note and extremely negative. Today, thankfully, we are seeing efforts from many publishers to amplify the voices of both Asian creators and Asian characters. Tokyo Rose: Zero Hour (out September 20th) is a highly informative case in point. Written by Andre Frattino, illustrated by Kate Kasenow, and lettered by the legendary Janice Chiang, it tells the story of Iva Toguri, an American citizen trapped in Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. She took a job with a radio station and eventually became the voice of a propagandistic radio broadcast. She earned the nickname “Tokyo Rose” from American soldiers who found her show amusing. Despite her lack of choice in the matter and her efforts to undermine the demoralizing intent of the broadcasts, Toguri spent several years in prison upon her return to the U.S., and her reputation has never fully recovered. Toguri’s story remains obscure, to the point where Kate Kasenow admits she knew nothing about it before beginning this project: “When Andre initially approached me with this idea, I had never heard of Iva Toguri but the name of Tokyo Rose did have baggage attached,” she told me. I had a similar experience: I had heard the name “Tokyo Rose” plenty of times, but not once did I think about who the woman behind the nickname really was. That’s why I was so excited to learn about this graphic novel. I was also excited to have the pleasure of interviewing all three creators about their sources of inspiration, their work process, and how they ensured that Tokyo Rose would be the accurate, sensitive portrayal that its subject deserves and has long been denied — and that their work would not add to the harm already being done to Asian Americans.

Japanese Characters in Comics: An Ugly History

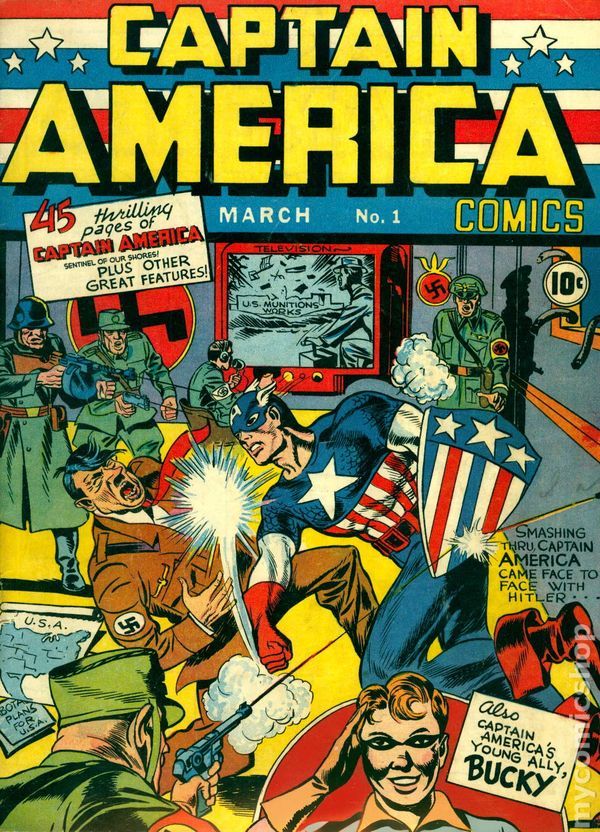

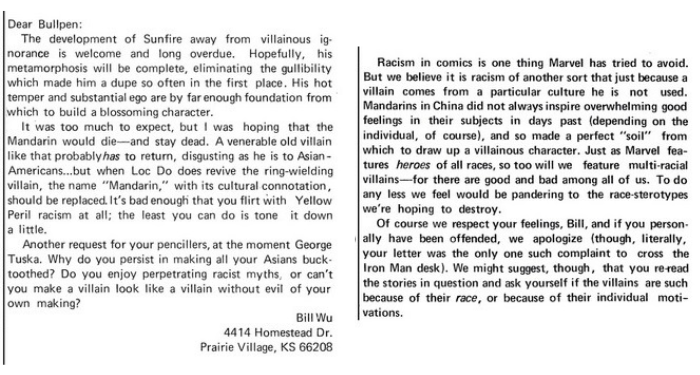

Superhero comics came into their own as World War II began — just in time to do what every other piece of American media was doing and demonize all Japanese and Japanese Americans as traitorous yet crafty backstabbers. I’ll spare you any actual images, because they are atrocious. Across the board, they depicted the Japanese as subhuman, demonic creatures rather than human beings. Our supposed heroes only added to this impression, gleefully spitting racial slurs at them and using more violence against Asian enemies than they would against even the most monstrous white Nazis. Iva Toguri lived in California when such comics were rolling off the presses. In a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scene from Tokyo Rose, her father is reading a Captain America comic (and enjoying it very much). According to Andre Frattino, the reference was intentional: That fact — that heroes like Captain America were “propaganda tools” as much as they were characters in their own right — explains why depictions of Japanese characters during World War II were so one-dimensional. They, too, were nothing more than propaganda. They were designed to confirm the readers’ (and the creators’) negative assumptions about the Japanese and Japanese Americans in the hopes of securing more support — financial, physical, and moral — for the war effort. Worst of all, there were no counter-narratives to combat these abominable depictions. No Japanese superheroes or, heaven forbid, ordinary folks just trying to live their lives. Every Japanese character was always a villain, period. Even after the war ended, comics continued to portray Asian characters in horrible, stereotypical ways. (For one example, check out the ’60s Wonder Woman villain, Egg Fu. For another, look at the history of Korean War comics.) When one Asian American reader wrote to Marvel complaining of this poor treatment, editor Stan Lee allowed the point to fly clear over his head and all but accused the reader of being racist himself. Janice Chiang, who is Chinese American, remembers facing unpleasant stereotypes as she began her career in comics. “When I began lettering comics, I would find stereotypes of Asian people distressing,” she told me. “One important breakthrough that writer and artist Larry Hama was able to institute was to [let] Asian people have flesh color skin tones instead of pure yellow.” That’s how low the bar was. Letting Asian people look like people was a revolutionary idea. Chiang herself had no say over how Asian characters were depicted: “As a letterer, I’m not in a position to make editorial decisions or changes on the script I am given to work on,” but as Asian American writers and artists like Larry Hama entered the industry, they were finally able to start taking the narrative back.

Japanese People in Comics Today

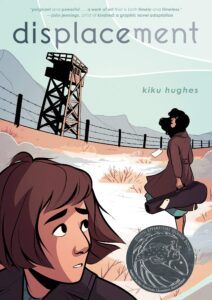

Today, there are even more AAPI creators than there were in the ’70s, and some of them have revisited World War II to tell the story of that era in their own way — a chance they were denied during the war itself. Kiku Hughes wrote and illustrated Displacement, a work of historical fiction in which a teenage girl (also named Kiku) goes back in time to witness the American government’s horrific decision to force 120,000 people of Japanese descent to stay in internment camps for the duration of the war. Star Trek‘s George Takei co-wrote the award-winning They Called Us Enemy, about his own experience in the internment camps. None of the creative team behind Tokyo Rose: Zero Hour is Japanese, so they took extra precautions to ensure they told Toguri’s story in a thoughtful way. To that end, Frattino hired sensitivity readers to review the book and offer feedback before it went to print. These readers are included in the credits in the back of the book, emphasizing just how critical they were to the creative process. “For me, if I was going to steward this story, it was absolutely vital to include people of Asian culture and heritage within it, to give them an ownership of it,” he said. As he explained it to me, this is why he invited Janice Chiang to contribute to the project, as well as why he looked for Japanese American creatives to review the comic before it was published. “I wanted them to see the power this book could possess with their help,” he said. Kate Kasenow was also meticulous as she sought to bring Toguri’s world to life. “Finding period imagery of Japan during this time was a bit difficult as their records are not only hard to access but much has been physically lost,” she told me. “I was fortunate enough to visit Tokyo many years ago, so I was able to gain some aesthetic imagery from my own photos, but I also did a lot of deep diving into museum archives and a few period piece films. I really, REALLY wanted to make sure I was portraying the Japanese people in a diverse and respectful way. I practiced facial sketches often and reached out to Japanese friends at the time to make sure I didn’t stray into caricature.”

Why Does it Matter?

As a comic book fan, I came at this from a somewhat narrow perspective: I compared Tokyo Rose‘s complex, sensitive, and sympathetic portrayal of Japanese and Japanese American characters with the unkind, demonizing depictions that dominated comics in the 1940s. But Frattino saw the bigger picture. “To me, this wasn’t so much an attempt to combat the negative depictions of Japanese and Japanese Americans SPECIFICALLY during WWII, but sadly, of the entirety of their portrayal even up to this date,” he said. As I mentioned in the introduction, anti-Asian hate crimes are still far higher than they were before 2020, so this broad approach is a wise one. Janice similarly referenced other media when she talked to me about historical depictions of Asian characters. She recalled speaking to Sandy King, film producer and wife of director John Carpenter. Chiang told King how she “was most impressed by the Asian actors who looked like me” in films like 1986’s Big Trouble in Little China. King responded by saying what “a real struggle” it was to convince the studio to go with Asian actors rather than putting white actors in yellowface make-up — a sign of how slowly times have changed and how pervasive anti-Asian racism is in American culture. Kasenow took a yet broader view of the matter. She believes that Toguri’s story can inspire readers to keep fighting in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. “There are so many problems in our modern lives that feel too big to conquer — too deep to even reach in a meaningful way, but each of us does have a part to play,” she said. “Small actions matter. They add up. Iva’s story helps me remember that and I’m honored to help spread that word with my art.” That, in sum, is the power of storytelling. It can inspire us to get through hard times and become greater versions of ourselves…or it can play to our worst fears and prejudices. The team behind Tokyo Rose put in the effort and hard work to ensure their graphic novel would be a force for good at time when the world sorely needs it. I honestly hope that everyone who works in any creative medium will learn from their example — and from the bad and hurtful decisions made in the past.