Despite how some may see the romance genre as just smutty bodice rippers, it includes, more than any other, consent. How did romance novels get this reputation when the community as a whole is so outspoken about people’s happiness, agency, and right to say no? We have to go back to the archives to understand the progression of a genre, and a movement over time, for the answer.

Where did this idea come from?

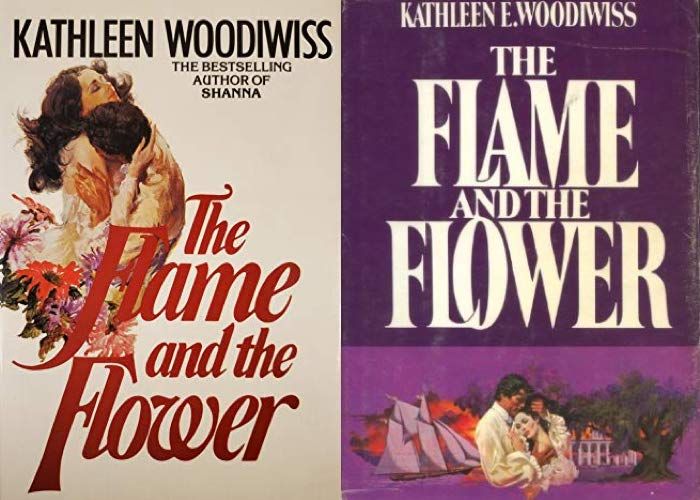

The term “bodice ripper” was first used in 1978 and, according to Merriam-Webster, is a historical or gothic romance typically featuring scenes in which the heroine is subjected to violence. The covers of historical romance novels of the time depicted women in gowns with corsets being held by men in sensual poses. One or both of them were likely to be partially naked. The primordial text that gave validity to this idea that romance is nonconsensual is The Flame and Flower, which is thought to be the first book of the bodice ripper genre. In this book published in 1972, the heroine is raped and eventually falls in love with her abuser for a happily ever after. Many romances to be written in the next two decades followed the same formula. In Julie Garwood’s The Bride (1989), the heroine is sold to a man because her father can’t afford to pay his taxes. Women being whisked away by sexy men against their will but having a happily ever after present a prime example of the “ends justify the means” argument. Romance critics today call these texts problematic at the least. Yes, there were consent issues in romances written in the 1970s and ’80s, but that’s likely because of the societal understanding of consent was different than it is today. Writers were writing for the moment they were living in. Just like I’m sure 20 years from today we will look back and see our contemporary romances in a new, hopefully more informed light. In 1972 when The Flame and the Flower was published, marital rape was still legal. Nebraska was the first state to outlaw marital rape in 1975, although the term “rape” wasn’t used. It wasn’t until 1993 that marital rape was outlawed in all 50 states; North Carolina was the final state to change its laws. The age of consent changing from state to state over time also contributed to ambiguous consent in early romance novels. In 1885, most states had the age of consent at 10 years old, with the youngest — looking at you Delaware — at 7 years old. At this time, age of consent was more about protecting a young girl’s virginity until marriage rather than protecting people from rape. By 1920, all the ages for consent had been raised, averaging between 16 and 18 years old. These laws were flawed and only protected girls, who weren’t the only victims of statutory rape. In the 1960s and ’70s advocates worked to change the laws to include all underaged persons. The idea of consent wasn’t at the forefront of society, much less publishing. So then how did such a problematic book like The Flame and the Flower start what is now a billion dollar industry? It depicted women’s pleasure. It was not usual at the time to show physical intimacy, especially when it involved women having pleasurable sexual experiences, on the page. Granted, the sex that was enjoyable for the heroine wasn’t until the last third of the book and was after she had been raped by her abuser multiple times and been impregnated by him. The sex was not consensual more often than it was in the book, and saying it is problematic is an understatement, but it still did something new for its time by showing that women could experience pleasure on page.

When did consent in romance start to change?

Just like in much of history, there’s a trend over time. In 1980, Gaywyck, the first gay gothic romance, was published. A turning point for the potential of what consensual love could look like and who could be included. The mid-1980s is where the change started gaining momentum, and by the 1990s romance started including conversations about consent en mass. According to Carol Thurston’s The Romance Revolution, during a 1985 Romance Writers of America conference, the consent debate about “what rape really is” got so heated that many of the participants walked out in protest. The change in the ’90s coincided with the 1990 institution of Antioch College’s Sexual Offense Prevention Policy. The policy came to be known as the Antioch Rules and was widely criticized around the country. The college became a laughing stock across the nation. As one of the creators of the policy, Cristelle Evans put it, “This went viral before viral was even a thing.” The satire went so far as to include a SNL skit called “Is it date rape?” that poked fun at the idea of positive consent during every step of a sexual encounter. It was considered unsexy and confusing. Around this time is when explicit consent in romance started to appear. In a previous article, I mentioned Susan Elizabeth Philip’s 1994 novel It Had to Be You, wherein the heroine, a rape survivor, tells the hero to stop over and over again during a sexual encounter. She’s sure that he won’t stop. The narration even says “she knew he had gone past the point where he would listen” but the hero stops every time she asks. Examples like this one were becoming commonplace in romance. Women were writing for other women, and LGBTQ+ folks for other LGBTQ+ folks. Love was being portrayed as exciting and mutual and respectful between two or more people. In 2006 survivor and activist Tarana Burke started the me too movement. In 2017, #MeToo had a resurgence worldwide after a viral tweet from Alyssa Milano that had many people talking about what consent really meant again, harkening back to the Antioch Rules of positive or enthusiastic consent. All the while, romance novels were sitting on shelves, often being scorned as smut and bodice rippers and trash, subversively teaching people what consent in romantic relationships could look like.

What about books without consent today?

While consent in romance overall has grown, there are certainly exceptions to the rule, with books that don’t include consent or where non-consent or dubious consent are the kink readers are looking for. People outside the genre or the kink communities might immediately think this means BDSM. They likely got this idea from the 50 Shades of Grey phenomenon that swept the nation in the mid-2010s. The characters in that book draw up an explicit contract, but the criticism of the series is vast, especially among those in the BDSM community where consent is a pillar of their beliefs. Dark romance, on the other hand, is an entire sub-genre full of non-consensual sex or dubious consent. Non-con, or consensual non-consent, is when characters engage in behaviors where one partner agrees to give up consent; dub-con is the gray area between enthusiastic consent and rape. The character hasn’t given explicit consent but may not consider the sexual encounter rape. Some romances are written specifically for readers looking to play out fantasies about kidnapping and rape. An example of this is Captive in the Dark by C.J. Roberts. In this book, Caleb is traumatized as a child when he is kidnapped by mobsters and forced to become a pleasure slave. In order to get revenge, he kidnaps an 18-year-old and trains her to be like he was. Olivia, the young woman he’s kidnapped, fights her attraction to him, but eventually succumbs to it. The important difference between this sub-genre and the rape seen in earlier novels is that the authors are intentionally writing books without consent as a sexual fantasy. In contrast, many novels in the beginning of the genre had rape throughout all sub-genres depicted as acceptable, so long as the hero and heroine ended up together in a happily ever after. Specific books about sexual fantasies versus women not knowing their own mind until a man shows them is a key distinction. Many people have complicated feelings about rape fantasy, and fiction can be a safe place to explore these feelings. An example of a dark romance that contains rape is Whispers in the Dark by LeTeisha Newton. The book is about a woman who is kept in a cage and falls in love with her captor’s son. She escapes and the son stops at nothing to find her, including killing his own father. The Fated Mates podcast has done an episode dedicated to dark romance and interviewed devoted readers of the sub-genre. Fated Mates also gives suggestions of books to read for those who want to be introduced to dark romance. It’s been a long, often troublesome journey for consent in romance novels. The same journey has been reflected in our society. People want to criticize romance for where it started and everything that was wrong with it through a 2021 lens. The thing is, we have to start somewhere. I’m not making excuses for romance’s past, but I am applauding the work the romance community has done since 1972 and the work it continues to do. We probably still have a long way to go, because the 2071 lens looking back at today will see problems we couldn’t have anticipated, or did know about but didn’t adequately address. I’m sure the genre will keep working to be better and to spread the message that everyone is deserving of love and respect. It will continue to share stories of people being listened to when they say “stop” and “no” or “yes” and “please.” If you liked reading this, chances are you’ll love What Does Consent Look Like In Romance? and 6 Reasons Romance Novels and Readers are the Best.