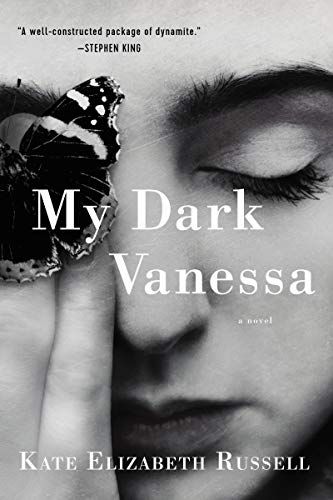

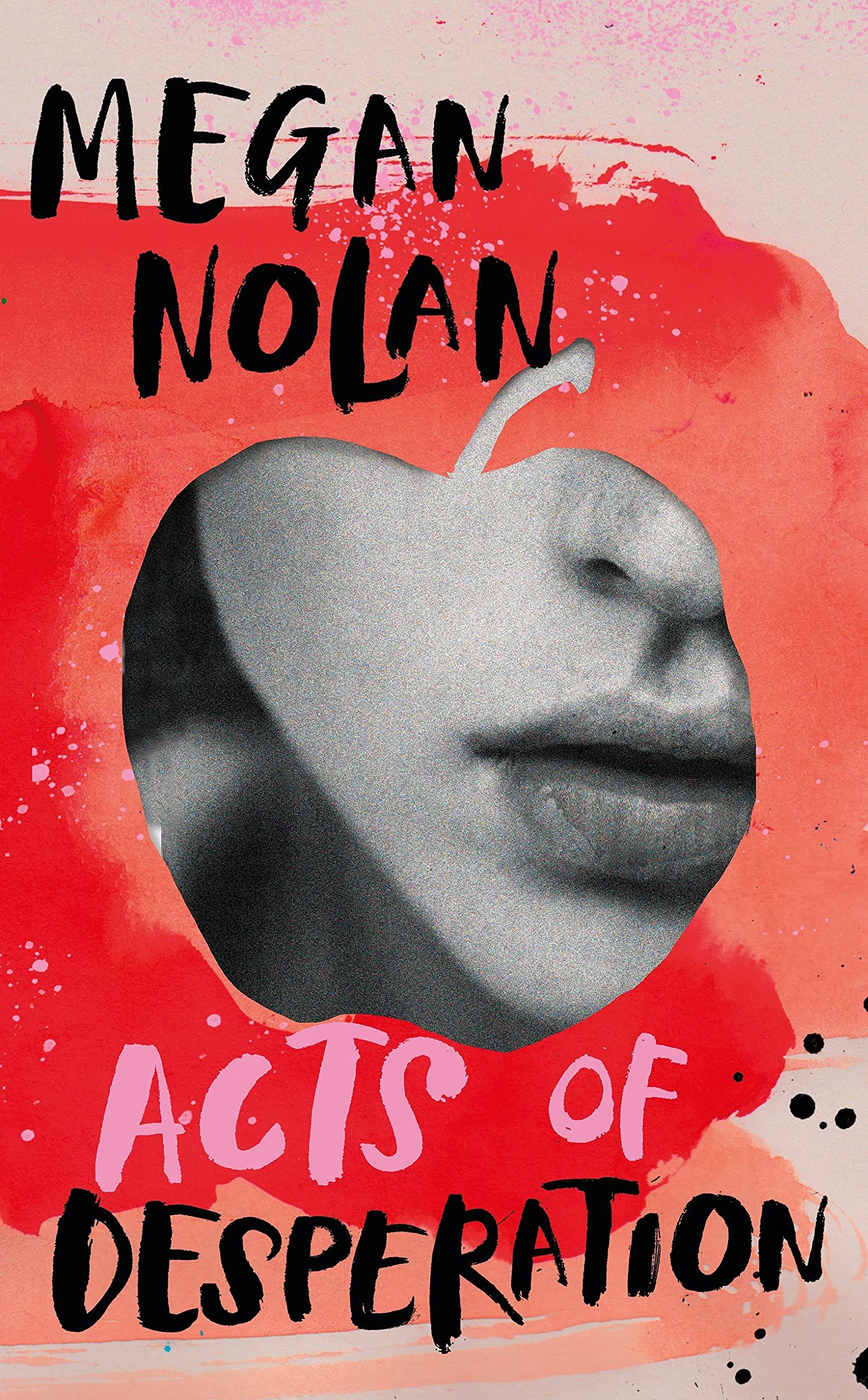

In Kate Elizabeth Russell’s My Dark Vanessa, 15-year-old Vanessa’s first love is her teacher, a 42-year-old Jacob. Jacob cleverly exploits her hormonal teenage mind and her deepest desire for admiration. He breaches all boundaries and starts touching her inappropriately in class, much to Vanessa’s pleasure. He quotes Nabokov and starts calling her “My Dark Vanessa.” He gifts her Lolita, which Vanessa becomes obsessed with to a point when she confuses her own memories with those of Lo and Humbert. The novel opens as an adult Vanessa tries to recount her ‘affair’ — if we can call it that — with Jacob. Vanessa still hasn’t admitted to herself that she has been sexually abused by Jacob. Instead, she remains fixated on him. Since her teenage years, she has been full of longing and desire for this monstrous man who repeatedly raped her in the past and is now seeking her support to defend him against allegations of sexual harassment. Vanessa says, “I wasn’t abused, not like that.” She strongly believes that she wasn’t “raped raped.” She adds, “All I can think of is the lovely warm feeling I’d get when he stroked my hair.” Vanessa is a classic victim who protects her abuser as the truth will break her. She is mad at the world that vilifies Jacob and still delusionally thinks that he was in love with her. One loves as one knows how, and for Vanessa, loving her abuser is a way of loving herself. She has a dull job and so much of her potential has been wasted because of her obsession with Jacob. Yet she has her sights set on Jacob as if he is the prize that will finally stabilize her life. Losing her desire for Jacob will mean losing a pivotal part of herself, something she has built her personality around. Vanessa’s constant denials of her own victimhood and her stark refusal to stop loving it signify the ambivalences inherent in abuser-abused relationships. Megan Nolan’s Acts Of Desperation is a tour de force chronicling the many paradoxes of female desire. The narrator is in her early 20s and in love with a man named Ciaran who is cold, casually cruel, and still in love with his ex-girlfriend. The narrator’s love for this man, the toxicity they share, and the way she feels the happiest in a sacrificial role leave the readers feeling claustrophobic and gasping for air. She willfully removes herself from her friends, narrowing her life down to revolve around Ciaran: cooking him effortful meals, the increasingly joyless sex they have, and the bottles of wine she downs when Ciaran isn’t there to monitor her. Though she revels in her victimhood, pushing herself to anorexia, and having periods where she cuts herself, she also longs to be free. Her desire to be debased by Ciaran stands in sharp contrast to her desire to evolve into an independent woman. The narrator writes: “When I sleep with men I don’t like, men who irritate or scare or disgust me, because it is easier to do so, I make myself as bad as they are.” The quest of the narrator is to learn to say no, to deny her own propensity for self-destruction and reject her own victimhood, and in the process, change the way women are viewed by patriarchy. The simplistic binaries of good or bad stopped existing a long time back. The narrator’s moral complexity and the state of her sexual affairs demand a more nuanced dissection. About a sexual partner, the narrator says, “He kept touching me and eventually I did what I had to do to stop him from wanting to have sex with me, which was to have sex with him.” It’s tragicomic, relatable, and heartbreaking how women navigate the patriarchy and cope with the sense of entitlement of cis het men. Nolan hasn’t assigned any names to her narrator as she is one of us: a self that eroticizes her own humiliation to survive patriarchy, and that every woman carries. A society that is bent on forcing female desire into oblivion doesn’t acknowledge that women too need and deserve affection. Therefore, there are women like Vanessa and Nolan’s unnamed protagonist who are so lonely that they welcome any kind of invasion into their lives. Literature depicts female desire for what it is, even when it is self-negating and even when it is accepting of all the indignities in the world. Literature doesn’t extoll female desire, nor does it patronize it. Rather it offers a platform where female desire is not shameful or illicit, regardless of its dark and morally ambiguous sides.