It would be another eight years before Tuck Everlasting would reenter my life and start making more sense to me. In college, as a Literature major, I had this unspoken habit at the beginning of every semester in the school bookstore: while browsing for the books I needed for my own classes, I would also tend to buy other books that I didn’t need for school, but rather for my own bookshelf. That year, I found Tuck Everlasting, the same edition that I read in 5th grade, and knew that I needed to buy it. Since it had been quite a while since I had read it last, I also decided that I was well overdue for a reread. At this point, I was in an awkward stage of life, poised on the line between childhood and adulthood. I was scared of growing up, so I retreated back into my childhood, staying there longer than I should have. But when I reread Tuck Everlasting—a children’s novel—I wasn’t burying my head in the sand and ignoring the newfound adult responsibilities that were piling up. Quite the opposite, actually. The novel’s themes of what it means to live forever and fearing the unlived life were in fact monumental in helping me begin to confront my anxiety over growing up and leading a fulfilled life. Tuck Everlasting follows young Winnie Foster, who is stifled by the expectations of her wealthy family in the small American town of Treegap. She meets a boy named Jesse Tuck one day in the woods, drinking from a spring. In an attempt to stop her from drinking the mysterious spring water, the Tucks kidnap Winnie and later explain that the spring water grants eternal life to anyone who drinks from it. Meanwhile, the family is being pursued by a man in a yellow suit, who has been searching for the Tucks for years in hopes of exposing their secret. While in hiding, Winnie grows fond of the family, particularly Jesse, and begins to debate whether she should drink from the spring in order to be with him forever. Winnie is 10 years old in Babbitt’s novel and 15 in the 2002 film adaptation. When I was 19, I didn’t yet know that it was okay to slow down or that it was okay to take breaks. I worked myself to the bone as a full-time student and used that as an excuse to not pursue part-time work or anything outside of being a student for several years. The thought of having to become a person made me so anxious and overwhelmed that I used school to shield me from having to grow up—from having to live my life. The only way of being that I knew was working like crazy to make everything perfect, and then not getting out of bed for two days afterward because I didn’t know how to deal with the resulting energy drain and burnout. This had been the only reality I’d known for most of my life. “It seemed to Winnie that the Tucks lived in a way that the rest of the world had forgotten,” speaks the narrator in the Disney film adaptation. “They were never in a hurry, and did things the slow way. For the first time, Winnie felt free to explore, to ask questions, to play.” Even though my parents used to tell me all the time as a child that life is not a competition, I didn’t really learn that for myself until recently. I was too caught up in the idea of life as a race, one that we all tend to struggle with more and more as time goes on (especially in the age of social media, when it feels like nothing ever sleeps—even though we’re humans, not machines). I was so busy racing, pushing myself to go faster and faster, but I never knew why or who I was competing against. I just thought that this is what adulthood was, even though it made me incredibly depressed.

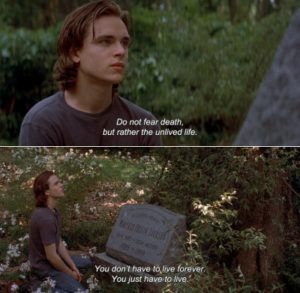

When I reread and rewatched Tuck Everlasting, it occurred to me that there was a lot of value in living like the Tucks—in a way that the rest of the world had forgotten, feeling free to explore, to ask questions, to play. (I also wouldn’t mind having a shirtless Jonathan Jackson hold me in his arms under a waterfall. Just saying.) But it also occurred to me that I don’t need any other excuses not to live my life. When life overwhelms me, I’ll retreat into the worlds of books, movies, and music where everything feels certain, comfortable, and where nothing will go wrong. But that’s not how life works. Things go wrong. Change happens. Nothing is certain. Nobody lives forever. And I can’t swim under a waterfall with a half-naked Jesse Tuck because he doesn’t exist. “There’s one thing I’ve learned about people, Winnie,” the Tuck patriarch, Angus, tells her in the film adaptation. “They’ll do anything, anything, not to die, and they’ll do anything to keep from living their life.” He also tells her that what the Tucks have, eternal life, cannot be considered living, they “just are,” like rocks stuck at the side of the stream. “I don’t wanna die, is that wrong?” Winnie asks. “No. No human does,” Angus replies. But you can’t have living without dying. “Don’t be afraid of death, Winnie. Be afraid of the unlived life.”

I think we have to achieve some sort of happy medium. A place where we are allowed to feel overwhelmed and take breaks and ignore reality for a while, but while also remaining acutely aware of the fact that we can’t ignore reality forever. That’s not living. No matter how strong a fortress we build, the cruelty of reality will always knock it down. So maybe we allow ourselves to take breaks and borrow a page from the Tucks’ book, where we slow things down and allow ourselves to explore, to ask questions, and to play. And once we’ve given ourselves a sufficient break to recuperate and feel like people again, we will feel more equipped to reenter reality and live our lives to the best of our abilities. I’m not saying it’s an unflawed method, since life tends to pull us in all different directions no matter how hard we try to adapt. But Tuck Everlasting’s wisdom helps me tremendously in toning down the anxious voices in my head, and I continue to return to it when it all feels too much.