It’s hard to think of a more modest introduction for someone who was gifted in so many ways in arts and literature. A Renaissance man, Ellison studied music and sculpting; he was a literary critic, an essayist, and a professional photographer. During the war, he was a merchant-seaman. And, oh yeah, he happened to be a brilliant fiction writer as well. When he died in 1994, he had completed just one novel — Invisible Man. But what a novel it was. Published in 1952, Ellison won the National Book Award the following year, beating Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. Ellison’s book has gone on to be considered one of the best, if not the best, post-war novel from last century in poll after poll.

Why Ralph Ellison’s Work Remains a Must-Read

Invisible Man is a searing portrayal of an unnamed Black man trying to find himself amidst the turmoil of 1930s Harlem. Readers learn in Ellison’s opening line what the narrator has already figured out: “I am an invisible man.” Why? “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.” Written while the United States was still in the midst of Jim Crow, Ellison’s work continues to be a powerful voice of this century. When Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black high-schooler, was shot by George Zimmerman, many people wrote that Ellison’s idea of invisibility still pertained today. Martin was invisible, not only to Zimmerman, but to members of the jury who ultimately sided with Zimmerman. Yet Ellison’s legacy is not without controversies. According to a 2012 article in The New Yorker, in his later years, he was accused of losing touch with his roots. He was also accused of not helping younger black writers. David Denby writes in the New Yorker, “As Ellison struggled, many people thought they had his number: he had ascended to fame, to honors, to establishment friends and clubs, and all of that finished him as a writer.” But Denby argues people are too focused on what he didn’t do — finish the second novel — and not enough on what he did. He created “a work of art that, as it happens, has never been more ‘relevant’ than now.” Besides, it wasn’t like Ellison quit public life after Invisible Man. He went on to complete numerous essays, including those complied in the books Shadow & Act and Going to the Territory. In 1969, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He taught at Bard College, the University of Chicago, and Rutgers University, and he served as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities at New York University for nearly a decade. Greg Thomas, a jazz columnist writing in The Root, said that throughout Ellison’s life, he defended Black American culture over race. “Ellison knew that race was built on surface perceptions that hid deeper human meaning and identities derived from culture,” he said. Thomas says it’s another reason why Ellison’s novel remains so resonant today. “The power of Invisible Man to still reach readers in their guts, hearts and minds — to relate to their sense of life, whether male or female, or from whatever ethnic or cultural background or nationality — is well-stated in the novel’s closing line: ‘Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?’” Ready for more? Here are 19 amazing facts about Ralph Ellison that show a lifetime filled with incredible facts and feats.

Ellison’s Early Life

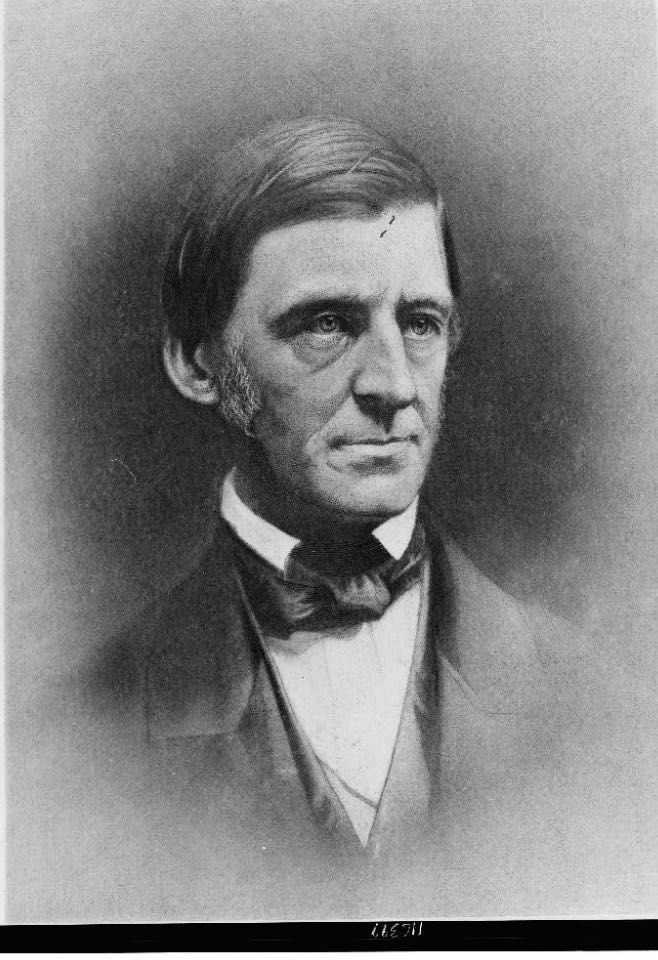

- Ralph Waldo Ellison was named after the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ellison was born in Oklahoma City in 1914. His father, Lewis, loved to read and named him after the 19th century essayist and poet. Unfortunately, Lewis Ellison died in an accident when Ellison was just 3 years old. Shards from a fallen 100-pound ice block pierced Lewis’s abdomen while he was delivering ice. Ellison writes in his first essay collection Shadow & Act that he would learn later in life that his father hoped he’d become a poet.

- As a teen, he worked a variety of jobs, including busboy, shoeshine, and waiter. After his father’s death, his mother Ida cleaned houses to make ends meet, but she supported Ellison’s early interest in music. He began to play the cornet at 8 and would later learn piano as well. After high school, he worked to buy his first trumpet. It was during this time, he began to immerse himself in the local jazz scene.

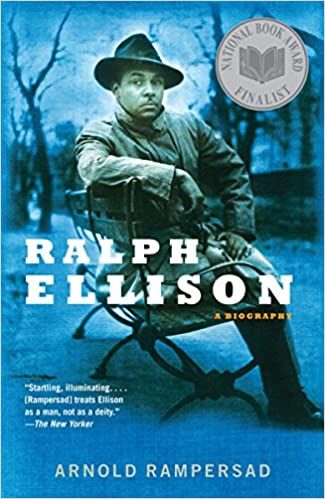

- In order to get to college, he had to hitch a ride on a train. Ellison won a scholarship to attend the Tuskegee Institute, but he didn’t have the money to get there. Desperate for a chance at college life, he ended up hopping a train to Alabama from his home in Oklahoma City. Arnold Rampersad writes in Ralph Ellison: A Biography, that Ellison’s mother was dismayed when Ellison announced how he was getting to school. Hoboing was dangerous, especially for Black men. But Ellison enlisted the help of a hobo named Charlie Miller, a man known for his drinking and gambling. With Miller’s guidance, he made it to college.

- He went to college to be a composer. Ellison loved jazz, but in college he had his eye on becoming a classical composer.

- Shadow & Act, his first collection of essays, is dedicated to his English professor from Tuskegee College. The dedication reads: “For Morteza Sprague, a dedicated dreamer in a land most strange.” Ellison said in Conversations with Ralph Ellison, “I consider Sprague a friend and dedicated my essays to him because he was an honest teacher.”

Ellison’s Writing Influences

- Ellison considered T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land an important influence. After reading The Waste Land in college, Ellison began investigating literary criticism and other writing about Eliot’s work, not realizing writing would become the driving force of his adult life. At the time, he still considered himself a musician, first and foremost.

- The novelist Richard Wright encouraged him to write his first short story. While in New York City, he met Richard Wright at a reading. Wright, who is best known for his novel Native Son, asked Ellison to write a book review for a magazine he was editing. Based on the review, Wright encouraged him to try writing a short story. Ellison did, and Wright wanted to publish it. Ellison said about the story in a 1955 interview with The Paris Review: “It got as far as the galley proofs when it was bumped from the issue because there was too much material. Just after that the magazine failed.”

- He met Richard Wright because of his new friend, the poet Langston Hughes. Ellison went to New York after his junior year at Tuskegee Institute to earn money, but he happened to meet Langston Hughes just after arriving. According to an article with the Library of Congress, that serendipitous encounter changed everything for Ellison. “The morning after my arrival in New York,” Ellison said, “I encountered figures standing in the entrance of the Harlem YMCA, two fateful figures. They were Langston Hughes, the poet, and Dr. Alain Locke, the then head of the philosophy department at Howard University.” Ellison continued: “Hughes wrote Richard Wright that there was a young Negro something-or-the-other in New York who wanted to meet him. The next thing I knew I received a postcard — which I still have — that said, ‘Dear Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes tells me that you’re interested in meeting me.’” Ellison never returned to college, instead staying in New York where he would eventually write Invisible Man.

On Surviving This American Life

- He once hunted to earn money. In the 1930s, he sold game in Dayton, Ohio, to make a living. Ellison told The Paris Review: “At night I practiced writing and studied Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Stein, and Hemingway. Especially Hemingway; I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story … but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird.”

- He later wrote about those hunting experiences in a short lyrical essay, titled “February,” published in the Saturday Review. While Ellison was living in Ohio, his mother died. In the Saturday Review essay, he wrote that, weary of grieving, he’d “gone into the woods to forget.” He found a perfect apple, left miraculously over winter, “sweet and mellow,” and it sparks a new mood of exhilaration: “For I was in my early twenties then … had survived three months off the fields and woods by my gun; through ice and snow and homelessness. And now in this windless February instant I had crossed over into a new phase of living. Shall I say it was in those February snows that I first became a man?”

- He credited President Roosevelt for helping his writing career. The Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) was part of Roosevelt’s New Deal. It gave many writers a way to pay the bills in the 1930s. In a 1963 interview with Allen Geller, Ellison said: “I first started writing under the WPA — that is I was able to give time to writing because I could do work for them and learn to do my own.” You can read some of his work with the WPA in the archive of the Library of Congress.

On Writing

- When he died, he’d been working on his second novel for more than 40 years. He left nearly 2,000 pages of an incomplete second novel. His longtime friend, John F. Callahan, edited and published those pages after he died. The novel Juneteenth was released in 2000. At one point, Ellison said he had to restart the novel from scratch after a fire in his house destroyed his copy, though his biographer, Rampersad, claims this wasn’t true. Rampersad said Ellison had “exaggerated the extent of the loss.” Ellison often spoke of his insecurities about his own writing. He noted he had all of the usual writer problems. “I write sometimes with great facility, but I question it; and I have a certain distrust of the easy flow of words.”

- He had a contract to write his first novel before he even knew what the book would be about. While still working as a merchant-seaman during the Second World War, a publisher contacted him. He had seen some of his short stories and essays and wanted to know what else he had. Eventually, the publisher asked if he had a novel. He did not. He asked if Ellison had one in mind. Again he said he did not. The publisher gave him a contract and a $1,500 advance anyway. Five years later, Invisible Man was born.

- There are many great quotes from Ellison’s novel. But here’s one on writing from the introduction to Shadow & Act: “The act of writing requires a constant plunging back into the shadow of the past where time hovers ghostlike.”

On Invisible Man

- Invisible Man contains one of the most beloved prologues of all time. Writers are often encouraged to ditch prologues these days, but it’s hard to read Ellison’s without absolute admiration. His prologue, considered “Joycean,” is a stunning musical revelation of a nameless man.

- The novel isn’t about him. Written in first person, he was often asked if the novel was autobiographical. It was not, though one could see how readers might think otherwise. The book is about a man from the American South who moves to Harlem. The narrator struggles with identity and briefly engages with the Communist Party. All of these things Ellison did in his life. Yet, as any writer knows, just because some of the big details are the same, it doesn’t mean you book is about you. In Conversations with Ralph Ellison, he said, “[It was] an attempt to see whether I could write the first person and make it interesting, make it dramatic and give it a strong dramatic drive.”

- The novel begins with the word “I” and ends with “you.” According to an article by W. Quentin Miller, a professor of English at Suffolk University, the ending forces the reader “to contemplate how connected they are to the stories of others … on a deeper level than they might realize.”

On Invisible Man … The Movie??

- In 2017, Hulu announced it was developing a series adaptation of Invisible Man. At the time, Hulu was running high off their recent success of another adaptation: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The Invisible Man adaptation was in early stages in 2017. No script or cast was announced. So far, no updates on the project have been released.

On Invisible Man … The Play

- In 2013, Invisible Man ran for the first time as a play. Oren Jacoby wrote the play with the strict instructions that not one word of Ellison’s original dialogue could be changed. He ended up with a three-hour-long production, but performances sold out in Chicago and Washington. Another slightly different version played to great success in Boston. According to a New York Times article, “the play ‘Invisible Man’ was developed over a year in workshops around the country. It had its premiere in a 250-seat house at the University of Chicago’s Court Theater. The six-week run … sold more tickets than any other nonmusical in the theater’s 52-year history. It went on to a sold-out, twice-extended run this fall in a 230-seat house at the Studio Theater in Washington, a coproduction with the Huntington.” Looking for more about Ralph Ellison’s life and times? Check out Conversations with Ralph Ellison for interviews and commentary in Ellison’s own words. For deeper research, try Ralph Ellison: A Biography. The book contains many stories behind the stories about Ellison’s fascinating life. Can’t get enough of author deep dives? Get to know a little more about Oscar Wilde, Sylvia Plath, O. Henry, Mark Twain, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Baldwin.